To celebrate the release of T. Fox Dunham’s new novel about the lost son of Andy Kaufman, we’ve published his Doctor Kevorkian novella here for free. Both Doctor Kevorkian Goes to Heaven and Searching for Andy Kaufman could be considered spiritual siblings, as they each deal with death in a very real and transcendental way. Fox is a fighter. He’s dealt with cancer his entire life. Read his words to know what it feels like to die. Read his words to know what it feels like to survive.

Doctor Jack Kevorkian died from thrombosis—crusader for the death of the incurable—on June 3rd 2011 at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan—at least this is what was reported to the media and family. The true story is far too gruesome and interesting to have been released to the public. When Doctor Kevorkian arrives in heaven, after creating an immortality engine, he meets God and suffers terrible disappointment, being an avowed atheist. On Earth, his old lawyer discovers the immortality invention and cures the world of the common death, and without death and sickness, he absolves the race of all motivation to grow. This is a story of human rights and why we as a species require death. This is a story of the end of the world. And this is the author’s story, of his fight with cancer and one day desire to end the pain through the grace of Doctor Kevorkian—a madman, healer and egomaniac.

After you give Doctor Kevorkian Goes to Heaven a read, we highly encourage you to pick up Destroying the Tangible Illusion of Reality; or, Searching for Andy Kaufman.

And don’t forget: you are going to die. And don’t forget: there’s nothing you can do to stop it.

Thou, silent form! dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.’

—Ode on a Grecian Urn

John Keats. 1795-1821

(Now a fading statue in Heaven.)

Doctor Jack Kevorkian died from thrombosis on June 3rd 2011, eight days after his 83rd birthday at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan—at least this is what was reported to the media and family. The true story is far too gruesome and interesting to have been released to the public. It can now be told, as it was told to me by his closest compatriots, his wee cadre of ghouls.

And so it came to be that before his death—tired of going to court for his noble work for responsible euthanasia and failing a run for governor—Doctor Kevorkian began work on inventing an immortality machine. He decided it would be of great value to society to obviate the question of mortality, so civilization would no longer be pestered by such antagonizing questions such as when is death death? And what is quality of life? And thus, with such questions no longer relevant, the world could go on happily buying consumer products and watching the latest episode of American Idol. These questions forced humans to exercise their frontal lobes. Humans went to places such as bars or pubs or churches to actively block stimulation of their frontal lobes, and for that reason so many brilliant men and women in history were locked away, often burned alive or poked with sticks or bullets.

Now when I say ‘invention’, I don’t necessarily mean a machine of moving cogs and sputtering sparks. Some of the finest inventions of human-making—those paragons of art and spirit that hinted and tormented that indeed the human machine might just possess some spark of the divine and thus it should survive its wars and cruelty—manifested in spiritual forms of art such as paintings, literature and music. Few knew that Doctor Kevorkian was a Philomath, a true renaissance man. When he wasn’t healing the sick through medicine or assisted suicide, the Good Doctor painted, often with his own bodily fluids, and he composed music, often in the key and tone of his one true god, Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach played a church organ. Doctor Kevorkian had a synthesizer in his little apartment where he could bang the keys and create logical rhythms that soothed his ear and perhaps soothed the ears of other humans, so they might feel good and not want to do things like drop gravity bombs and fire guided missiles at impoverished villages in the desert that just happen to be built on black decayed plant matter. The other human pastime besides singing lullabies to their frontal lobes was pumping out decayed plant matter in the form of crude oil, which they then burned in machines that took them places. Humans loved to go faraway places, and this required a lot of the decayed plant matter.

The idea for an immortality engine had circulated his thoughts since his youth. The nothing first smacked him like a low-flying blind buzzard while he served as an Army medical officer during the Korean Police Action. (Not a war.) He’d grown furious watching Korean children die when blood supplies ran out and watching the devastation of the Korean county, and after suffering constant nightmares of the Armenian massacres that drove his family from their country, he determined that there must be a way to end humanity’s addiction with dropping bombs from jets and shooting holes in healthy bodies with slugs of lead propelled to lethal speeds by rapidly expanding gas. He knew the sedative effect music held over him, especially the classic pieces of his god, Bach, and he determined that as a doctor it was his duty to humanity to achieve a piece of music that would fill human hearts with such joy that would come together and no longer fight over things like religion or who was allowed to sell hotdogs. In countries that practice a form of government called Communism, the state told the people who owned the hotdogs and who could sell them. This upset capitalist countries who wanted to own all the hotdogs. More people were killed during the Cold War over hotdogs than the pigs slaughtered to make them. This affronted Jack Kevorkian, who came to believe that poverty and mortality drove all war, and if death could be cured, so perhaps could war and practically all physical suffering.

Still, the project proved arduous, and he turned to more practical work that could carve his name in the giant kidney stone of medical achievement. He retired the idea and moved onto to find the potential in problems that faced him everyday working at the hospitals, like transfusing blood from cadavers—a procedure he tried to sell to the US Military but had little success—and determining an exact time of death by studying physical responses in the body. This little man with a head like a shaved orange danced about on knobby toes, looking to contribute to the world of science, to make his mark and be remembered—granted the mantle of immortality in history and medical books of record. For what other form of immortality could one desire? Not when time decays, destroys, rots and mutilates all things, even memory. He desired to perhaps be called upon one day through cries of desperation and jealousy upon the old masters: Galen. Plato. Galileo. Jenner. And Kevorkian!

That funny little man did have an indelible name.

* * *

Galileo was this bloke who when everyone else in Italy kept their eyes level at the ground or cobblestone streets or were looking away from plague victims or of church persecution, he kept his peepers peeped up at the sky, especially at night. Sometimes in church when he was supposed to be praying to this fellow who sat on the sky like a throne, he’d be cogitating upon all His great works instead. He defied Plato and said the Earth goes around the sun, then told some of those people in church. They made him take it all back, under pain of death, even though Plato was a pagan and not at all affiliated with the Vatican. Poor old Galileo. How much Doctor Kevorkian wanted to be persecuted like him.

And so Doctor Kevorkian found his cause: euthanasia, ending the life and suffering of those so ill they were beyond modern medical science. He fought this cause bravely, curing many of painful life, and eventually, the state locked him up to fade away and die. After they released the little doc out of prison—if he promised to be very good and not lead a revolution—he kept himself occupied. He ran for governor, mostly missing the public attention and a platform on which to fight his issues, and he painted macabre masterpieces with his bodily fluids and even sat down to tinker with concertos. Sitting in his pajamas one morning, he remembered his idea to write a song to create a cure for the common mortality. Music had always possessed such inspiration for him and humans in general. It connected the soul to the body, engendering such forces as love and melancholy. It could heal and destroy, and he always suspected that it possessed certain physical qualities that imbued the body with new life and motivation to keep going. A good song possessed the power to heal.

Doctor Kevorkian labored over this new concerto, keeping it simple, easy to play so a layman could hammer it out on any old tinny piano out of tune. He didn’t want the formula to belong only to the genius musicale, the high elite, who would bottle and sell it to the desperate, which is what had happened to so many salubrious and preserving medicines that could improve the quality of life for the millions sick. The song had to remain simple, and he worked along the theme of a child’s nursery rhyme, a song that could be hummed in the shower by even those tone-deaf.

He closed his eyes when he composed and searched for the heart of music. In every song composed, the composer seeks the source, a living and beating heart. The ancient Bards called this the Awen, a spiritual organ that generated all art and creation, and he studied the work of ancient Bards, seeking this Awen, to bottle it up and distribute it free in his song. His mind took apart the math, worked the equations, and he remembered the moment of complete serenity that flowed over the faces of his patients as he guided them into death—when all the pain and regret washed away, leaving only the good memories. It left no more heartbreak: only the sweet love that came before.

“Heaven is when you only remember the joy and let go the ache,” T. Fox Dunham—a cancer patient who lived in agony everyday—wrote many miles away.

Doctor Jack Kevorkian had known heartache once. She had worked at a department store in his youth, and he’d given her an engagement ring, even though he couldn’t be sure what love was. The equation didn’t balance, and he promised himself he’d devout his life to science and seeking meaning. He liked equations that balanced.

In his quest for this immortality song, he looked to his youth when he’d adored all classical composers, rejecting the music of his age in favor of the traditional logic and math of Beethoven, Handel, Chopin and of course Bach. He adored the sheer simplicity, the equations at balance and the planets in harmony above in the night sky. Once, he’d borrowed as many record players as he could find and played all the great composers at once, in simultaneous synergy: Beethoven, Mozart, Handel and many others—and leading above all, the great music of life, the best music composed in the human age was Bach. His God. His mentor. He’d deified him and praised him above all others and worshiped his religion—of logic and music, in the order found in the human spirit that could summon such beauty and inspiration. No other composer would ever rise to his standard, climb to his peak, and the good Doctor Kevorkian played the MP3 on his laptop and listened to the soft key-falls of the Goldberg Variations, suffusing through the sweet sound. He drew from this for inspiration, and he wondered was he creating the music, or was the music creating him? Perhaps a little of both.

If human kind could create such music, then the race still possessed beauty. If it possessed such beauty, then there must be hope.

He played music from Beethoven, overlapping it with Bach. And still he played even more Bach. He added Mozart to the mix. He listened to the chaotic mix of concertos, studied the rapid percussion of strings. The chimes and thrums mixed into a cacophony that may have created a harmony, yet the music missed certain elements. He could hear the holes in the pattern, so he played more symphonies and concertos, adjusting the tempos and volumes. He searched the noise, the blend of styles and swore he could he hear a rhythm, a song just below the noise.

He allowed the mixed music to flow deeply into his body, adjusting songs, adding new melodies and canceling old ones. He experimented for weeks, not leaving his apartment, not stopping to eat or sleep, thus making a congestive heart issue even worse. But he was getting closer to some essential melody, the heart of all music, the core of the Awen. He would discover the root, the key, the foundation. It would go much further than music, for if he had done the same with literature, he would have discovered a written equation or a similar paradigm of symbols in combined and digested art. Humans must have been painting and writing and composing for this equation since life evolved intelligence. It beamed like a beacon across the dark sea, drawing the human mind toward knowledge and true enlightenment.

He locked himself away in his apartment and ignored the world. His friends banged on his door, and he yelled at them to go away. “Neal. I’ve found it. The life equation! I can’t be disturbed.”

Finally, he heard it: the perfect harmony—sifted and sieved out of that cacophony of sound and rhythm. He generated the notes on paper, copying what he heard, assigning it symbols and then numbers in the equation. Each side canceled out, reaching perfect equality. He hadn’t slept in weeks or eaten, and he drank coffee, needing to stay awake. Doctor Kevorkian kept a journal to record his progress for posterity. He composed the last note, and his heart ceased. Doctor Jack Kevorkian died that moment, holding a pen in his hand. It fell to his cheek, and his landlord found the shriveled-up little raisin of a man with a pool of black ink staining his jowl. He died with his pecker up.

* * *

I shout my story to the sun; It’s all there is left to do. I can’t bring my lost ones back to this world, nor can I bring back myself; however, I can keep laying down prose like planting thorn bushes. No one may read this. Everyone might. I cast it into your oceans like a message in a bottle. I have no vanity. Pain destroyed my ego.

There’s a reason I choose to write this story. Doctor Jack Kevorkian may have been a sensationalist, an egomaniac, even a murderer, but like so many devils in history, he fought for the right cause:

My freedom to die.

You’ll probably remember Doctor Jack Kevorkian, best known by his moniker, Doctor Death. I’ve known many doctors during my battle with cancer, and they could all be referred to as Doctor Death. They bill you when they kill you too. Doctor Kevorkian didn’t bill his patients.

This means YOU, assholes.

Doctor Kevorkian recognized that there was still dignity in living and that quality of life should be the only criteria which society used to define life and death. He desired to end suffering when the suffering becomes so unbearable that all quality of life is gone. He knew that life is just a big meat machine pursuing chemical processes; and as humans, we’d granted life spirit—something more than just a biological process. This spirit had to be protected and preserved with dignity and respect, or it would destroy consideration for life.

So this dear man crusaded to stop the perversion of life through artificial extensions—the keeping viable of human meat that should have been allowed to expire. His patients begged him. They understood agony.

I know pain.

I know the kind of pain that no longer that overwhelms your body in such intensity and complexity, like boiling water dripping into every mountain crack, that it is no longer pain, as pain is a differing sensation to the normal feelings of your bone and flesh. The pain replaces your continual state, and it destroys your mind. You can no longer think. All you can consider is the agony—sans one consideration: relief. When will it end? It must end.

Cancer destroyed my body before I became man, as it does with so many that people. I paid a price—The Price. I call it that now. It is a term for all the cost I must pay as I progress with my half-life. I am an isotope throwing neutrons. I dissipate. I die slower. As the pain progresses, I am grateful to Jack Kevorkian, the cause he represented.

During cancer, I didn’t keep my pecker up. I keep it up now whenever I can. I never know when it’s going to be the last time. Cancer broke my human machine and upset the natural process of chemical reaction that keeps my human meat viable and fresh. As my life progresses, my body deteriorates and breaks down, decaying as I live. Pain is an illusion yet it is constant, and I can no longer recall what it feels like not to be in pain. I am reaching a point where my quality of life will be so diminished that I will desire to emancipate myself and end the chemical processes that keeps my damaged meat viable. I’m no longer fresh, and I honor Doctor Kevorkian for his crusade to end my suffering. There are nights when I’d beg him too.

I’m keeping my pecker up, but when it sags and falls like soggy rose blossoms, I will call upon the practice of Doctor Kevorkian. That time may be approaching.

I will be ‘done.’

* * *

On June 4th, 2011, Doctor Kevorkian landed in Heaven. As Jack was an avowed—and obnoxious—atheist, this proved upsetting. His long feet and knobby toes touched down on nebulous cloud, and he jumped to discover that in the course of landing, angels had put a pair of pink bunny slippers on his feet. He arrived entirely naked, except of course for the slippers and clutching a brown train ticket in between his thumb and forefinger. He gazed upon the pearly gates, heard the choir of angels singing, and saw the face of God burning like a sun, so bright and furious that it would fast melt the eyes of any mortal on Earth. It drove daggers into his ethereal orbs, and Doctor Kevorkian stamped his new bunny-slippered feet and defied:

“I don’t believe in you, Sir.”

The old Doc kicked off his bunny slippers. The angels stopped flying and landed. The choir stopped singing. The sun burned. God roared and shook the heavens and Earth. On Earth, the living registered his voice as 9.1 earthquakes, though most of them hit the ocean floor, and his voice knocked a meteor out of its orbit around Jupiter and threw it at the Earth where it would enter into the lives of three authors.

“And where were you when I made the Earth and seas? When I drew the sky from the blue paint?”

The sun seared the doctor’s vision. “Could you, maybe? It’s so bright. My eyes are quite light sensitive.”

God sighed, and the clouds rained. Planes in India flooded. “I am the Lord thy God. I am.”

“Yeah. I got that. But it would just be so much easier to talk to you if . . ..”

The sun extinguished. The heavens darkened. A small stubby man climbed down from the circular hole in the horizon. His girth caused him to wobble as he descended the ladder, and his gut hung over his white trousers like a sack of drowned kittens. God set foot on the cloud, rubbed his fingers through the growth of wild beer and hung his chunky shoulders over. “I’m sorry. You caught me on the way to the shower. But is that better?”

“Thank you. You’re very polite for a delusion.”

“I’m no delusion.”

“You’re certainly no supreme being.”

The angels shuddered, and the choir dispersed, running from the wrath of the Old Testament Jehovah—just in case. Fortunately, God had mellowed in the last few millenniums and developed a sense of humor. The old God used to be so insecure and couldn’t stand even a little doubt, which he usually remedied through plagues and floods.

“I created you,” God said and scratched his crotch. God’s appearance reviled Doctor Kevorkian so much that he bent over and wretched, gagging on vomit, even though the response was entirely in his mind, since he no longer possessed a stomach.

“And I made a turkey sandwich this morning. Does that make me a divinity too?”

God considered this for a moment and lightning bolts forked from the clouds. The Heavens trembled. “All things came from me.”

“Then you are no God. A true God wouldn’t allow the suffering I have witnessed. Where were your hands in Korea when all those innocent civilians died? And what of the holocaust in Turkey? My family butchered?”

“Everyone is innocent.”

“And I have looked into the pain of my patients’ eyes as they suffered the long and terrible last stages of their diseases, trapped in that terrible limbo and praying for relief. It came into me, and I freed them. I did your work for you. You’re an absent father. A deadbeat.”

“And what of you? Who would take my place? Did you free all those who suffered? Did you cure all their pain?”

Doctor Kevorkian sighed. His ears itched, but he didn’t scratch. “They put me in prison. They hung me on a cross.”

“Not so easy being a God, is it?”

Doctor Kevorkian shrugged and refused to continue the argument with a manifestation of madness—anyway, the delusion had hit him with a solid point, and he hated being out-debated. God waited for his response, shrugged and parted company to go take care of vital matters of cosmic bookkeeping. Before He returned to His burning bright throne, he said to Doctor Kevorkian: “Keep your pecker up.”

* * *

The next day—at least day as Heaven measured time—Doctor Kevorkian calmed and considered his place in the cosmos. God stepped down from the sun to continue their debate.

“So if there’s a Heaven, which I’m not admitting to. This could all be a delusion of the mind in the last seconds of life. Time is perceived by consciousness and can be slowed or hastened. I could be lying in a hospital bed right now as the electrical impulses of my brain shut down—and to make me feel better, my brain is playing me a fantasy movie about the supreme being and life eternal.”

“Could be,” God said. He scratched at his toes through his sandals. “I sometimes question whether I’m real. But if this is all a delusion and it lasts forever, what’s the difference?”

“I can’t accept that. Reality has substance. It can be changed. New events can be set into motion. I wrote a song before I died, and it causes life eternal. It’ll change all human actions in the future and their influence on the universe.”

God shrugged. “I wish I could make you feel better. I really do. I can never seem to make anyone feel better. I didn’t invent misery. It just happened. It spread like an unintended variation in a virus. I don’t cause human suffering, and I’m sure inert when it comes to aiding it. It defines you. Death. Your creation of hell.”

Doctor Kevorkian sat on the edge of the cloudbank and looked at the blue world far far below. It wasn’t really there in that layer of reality, but he imagined he could see it, could watch the transactions of human life.

“So there is a hell?” Doctor Kevorkian asked. “Not that I’m admitting this is real.”

“Oh yes. There’s always been a hell, for as far as I could remember—and that’s all time and before. But it’s not a part of my design. It exists as long as the mind considers and cogitates and the heart feels.”

“Is it all fire and brimstone?”

“It’s different for everyone, buried deep in the body and soul. I’m afraid of it.”

Doctor Kevorkian leaned over the side of the cloud, trying to get a closer view like a watching satellite. Still his eyes would not adjust, and he felt so very far away from the place of meaning, of cosmic influence where his actions could change. Where he could make a difference. “Can I see it? It would help me to understand the relationships in the universe, of life and death.”

And God sighed. “You’re already there. Just close your eyes and feel what you fear.”

Doctor Kevorkian understood as if by instinct, some folk or soul memory shared among all life. He shut his eyes and let himself go, releasing to that child spirit he once possessed and now buried so deeply. The child knew the way to hell, and he followed him. Doctor Kevorkian arrived in Turkey.

Doctor Kevorkian had heard the stories from his parents, his grandparents. Only a few of his relatives had gotten out of Turkey alive. The stories terrified him as a child. The world fought its first joint war across Europe. Armenians lived under Ottoman rule, one of the empires fighting in the war club. He joined the body of a simple man, a teacher with a family—a wife and two daughters—living a simple life. Good people. Kind. Humble. They loved God and worshiped him.

Why do they hate us so much? It is only a rumor. Civilized people do not act this way. They’ve arrested two-hundred and fifty political leaders, teachers, priests. They will not come here. They will not hurt my family.

The military came, soldiers knocking down doors in Constantinople—the ancient capital of Rome, a holy city, a font of civilization. Soldiers marched his family from their old home of generations, the rooms where his parents, he and his children had been born. The pushed their bayonets into their backs, pushing them down the streets and out, out from the city where the common folk could see. They ransacked their homes behind them and marched his family along with thousands of other families to the desert, to the hot desert, burning his mouth. His daughters cried for water. The sun seared their skin, and still they’re forced to march, burning while the world burns in war.

On the sands, he held his daughters close, protecting them from the soldiers; however, he is but one man with ideas and not guns or swords. They pried his daughters away from his arms, breaking his shoulder and drove a bayonet into his thigh. The father watched as the soldiers raped his two daughters, again and again, driving their fragile body into the sand.

“It’ll be over soon.” He tried to comfort them. The blood poured from his body, feeding the desert. Then, he slept with his family forever in the sand.

* * *

Two years later after missing a red blotch on my arm, my doctors diagnosed me with Lyme disease; and thus began a battle that would destroy my body. They administered seven months of I.V. antibiotics, which probably had no real salutary effect after the first month; however, these medical professionals were too arrogant to admit that they couldn’t cure my infection. It wrecked my immune system, pushed my body over the edge. I trusted my doctors. Why would they do anything to harm me? We’re trained in America to be submissive to doctors, even though we should be the dominant ones as patients. I shaved that night at midnight, two nights before returning to school, so I know my face felt flat at 12.20 AM. I checked my cheek, right below my ear, to make sure I had cut close, and I found a golf ball growing beside my jaw.

Doctor Bishop (I’m naming my doctors chess pieces) scheduled surgery three days later. He knew it had to be soon. In that short time, I grew into my face—how far he wouldn’t know until he cut me wide. On that third day, they put me asleep, promising me a short surgery, an hour or two. I woke up several hours later with a strap securing my head tight and a tube draining fluid from my face. The mass had grown deep into my face, and he had to remove much of the left side. I lost glands, bone, muscle and skin; fortunately, Doctor Bishop practiced a successful plastic surgery sideline in addition to his primary medicine. He rebuilt my face, hid the scar behind me ear; yet, I still feel it inside. No one sees, but I can feel the holes. I refuse tongues when I’m kissed. I don’t want anyone to feel what I feel every day.

He didn’t know what it was. Cuttings would be cut. Slides would be placed on glass slides. It would be examined by the best labs. I waited.

Cancer is waiting.

It took them precious months to diagnose. On my next trip to see Doctor Bishop, he told me that my cells had to be sent to three different facilities, that they couldn’t be identified. I went back with the expectation that I’d be fine.

“Its cancer, lymphoma.” He gave me moment to absorb it. You never absorb it. The world, inversed, focused inward. I looked at the room, my doctor, my mother down the opposite end of a telescope. Reality shrank. I couldn’t hear them talking anymore—something about two cell types, a rare combination. “A mix of both Hodgkins and Large Cell lymphoma.”

Large cell burns through you in months. I knew from his voice I had little hope of survival. I didn’t understand it though. I wouldn’t understand the dire circumstances of my situation for years, if I survived.

If there are bastards controlling our fates, they tried to kill me. I shouldn’t feel special or paranoid though. They’re trying to kill all of us.

Keep trying you bastards. I won’t give in. You’ll have to take me cell by cell.

* * *

Throughout this tale, as it was told to me by my madness, I use the phrase, “Keep your pecker up!” This has become my battle cry as I work, struggling against intense fatigue and terrible pain as the damage from the radiation to my neck, head and back progresses, destroying my body. I’m in so much pain, and a time approaches when the qualities of my life will not justify this suffering, when this agony will consume me beyond the reach of high doses of morphine and fentanyl patches glued to my burned back. When that time comes, I will call upon the spirit of Doctor Kevorkian. He will comfort me and give me an end, and I confess, that at night when my kidneys and nerves won’t let me sleep, lasting weeks, and I come apart from lack of rest, the thought of ending my own life does not frighten me. It comforts.

What the hell does anything matter? We’re all motes floating on the backs of motes in the dark bitter void between unforgiving suns. All matter decays. Pattern degrades. Will fails. It is inevitable.

So what the hell? This is what I’m trying to tell a warlike world:

Put down that fucking gun and pick up a Long Island Ice Tea.

* * *

Doctor Kevorkian wandered about the cloudy realm of angels and altitude, catching an occasional stray glance at the far far Earth below like looking out an airplane portal, and he sighed. The dead and heavenly hosts considered not the future here. Nothing they did had an impact on the course of history or human events. He never admitted that this was indeed an afterlife, that all of this, his still active consciousness and awareness wasn’t just the few seconds of his life stretched out through a slowed perception of time, but he figured while he was here and he had to keep busy or petrify into stone from boredom and stasis. He always had to keep busy.

So he found stuff to do around the joint, work that in his opinion had been left far too long neglected and needed repairing, in order to keep this delusional world functioning at first-rate capacity. When the angels slept in the clouds, he’d sneak up and adjust the clockwork of their wings, aligning them better and oiling the gears. This soon caused issues, as the angels, unprepared for these calibrations, would launch with such velocity that they’d hit astral bodies and break their halos. So Doctor Kevorkian was admonished and forbidden from tampering with angelic wings. So he took it upon himself to refine and rake the clouds, aligning the dust motes with great efficiency and thus improving the rainfall. Over the next weeks, flood victims arrived from various areas of Asia and India, victims of out-of-season monsoons. They forbade him to play with the clouds.

Finally, Doctor Kevorkian threw stones at the burning seat of the Creator, calling him down to answer his complaints. God had yet to shave and grew white whiskers out of his jowls, and he carried a can of beer. It reminded Doctor Jack of Jerry Garcia, and he meant to ask if God had been the lead singer of the Grateful Dead.

“I cannot tolerate this stasis!”

God sighed. “I don’t often have this kind of stomachache from one of my creations. Aren’t you glad for the rest? You no longer have to worry about things like money or sickness.”

“There’s nothing for me to do!”

“What did you like to do on Earth? You were some sort of healer, right?”

And this took Doctor Jack back a bit, and he gasped. “Don’t you know? Wasn’t I violating your natural laws? Religious groups used to protest my house. I said you were imagined!”

God shrugged and sipped from his brewski. “I wasn’t really paying attention. Most of what you do on Earth is your business. I just want you to be cool to each other and not mess the place up too much.”

“And that’s it?” Doctor Kevorkian pouted, hunching over his shoulders, and he sat on the cloudbank and played with his toes. His stomach dropped out of his spiritual body.

“Don’t take it so hard,” God said. “I’ve got my mind on some big things.”

“You never saw my work? Never wanted to damn my soul to hell for the blasphemies I’d unleashed in the name or mercy and compassion?”

God shrugged. Doctor Kevorkian had to sit down. His head wobbled, though again it was all a mental illusion, considering he no longer had blood pressure that could drop. He sighed and considered his life. Had he made any contribution at all? The Supreme Court never heard his case. Doctors still can’t technically commit euthanasia. What had he really done? No sons lived to carry on the family name. But all hope may not have been lost. Perhaps his death might stir things up.

“Can I watch the Earth? See the events transpiring after my death?”

“It drives most insane.”

“I still don’t think this place is even real.”

God pointed at a valley in the beclouded landscape, several leagues away. Doctor Kevorkian got up, took one step, and he arrived, scaling the distance in one movement. The place appeared to be an inverted telescope. In this case, the telescope dug into the cloud and faced below at the living world. Doctor Kevorkian stepped inside the inverted dome and sat on a bean bag chair in front of the tiny lens. It took him some practice to focus the scope, at first free-ranging his view all over the world—a village in Moscow, a fishing boat off Brazil, long white snowbanks in Antarctic. Finally, he focused on Michigan and watched the events taking place. A dial could be turned on the lens that not only displayed space but also time, and he turned back the clock, counting back the days to just after his death. Then he watched and tried not to go mad.

* * *

My first oncologist, Doctor Pawn, conducted my chemo—a real asshole—tricked me into my first night of being burned by the industrial chemicals. You always want an asshole to fight for your life. I wasn’t prepared. I thought I was starting chemo the next day. Never trust your damn doctors, not now, not in America, and not ever. I wouldn’t have trusted Kevorkian when I went to him. And I would have gone to him in time.

So Doctor Pawn said: “Ok Tim. Let’s go. Let’s do it now.” They called me Tim before they called me Fox. I never cared for the name, and cancer killed Tim. He led me back to the chemo room: a circle of special chairs with I.V. poles, chairs that contain the dying. When you have cancer, you are the dying.

I wasn’t scared. I didn’t cry. I was nineteen and had no idea what to expect. They can’t prepare for you for it, but I knew it felt wrong for someone my age to suffer lymphoma. I sat down in that execution chair with so many ghosts at elbow. The old sat with me that Friday night. They inserted a tube into my arm. It pierced straight through. The nurse brought over the toxic chemicals, and she wore industrial rubber gloves to prevent from toxic exposure. She injected the poisons into me.

The cure destroys you, not the cancer. I didn’t understand how much chemo they injected into me because of my rare cell-type—treatment prepared by some of the world’s top oncologists. At first, you feel like a toxic chemical poisons you. I knew the nausea that came, but I didn’t understand the intensity.

For the next week, I vomited once every thirty minutes. The chemo kills fast growing cells in your body. Cancer is a fast growing cell, as is your hair follicles, stomach lining, white cells and sperm. First, you’re poisoned and vomited constantly. A week later, it lifts, and you eat everything. Then your white cells die. If you run even a slight fever, you have to go into reverse isolation until they can raise your white cell count. You recover and start again. Smashing my body with a hammer probably would have been just as effective.

It burned my ass out of the world. The chemicals seared me, devouring me, and every three weeks, I allowed them to do it to me again. And I allowed it, betraying myself. I don’t think I’ll ever forgive me.

C.H.O.P.:

Cytoxan

Adriamycin

Vincristine

Prednisone

* * *

A meteor breaking up in the Earth’s atmosphere temporarily interrupted his clear vision, as Doctor Kevorkian viewed the live drama that was the world after Jack Kevorkian had departed from it. It hadn’t stopped. It kept turning and forgot him.

He watched his little apartment. His lawyer came to clear out his stuff, mostly throwing out his papers, along with many of his books and pieces of furniture, chucking them all in a bin outside with the help of some guys. The milquetoast lawyer in the pair of rattlesnake skin boots regarded little for the doctor’s old possessions, and Doctor Kevorkian gritted his teeth watching the carelessness with which they handled everything he’d owned in the world. Finally, the lawyer came to the musical notations Kevorkian composed in the final moments of his life. The lawyer balled it up, ready to toss it into the bin . Doctor Kevorkian nearly swallowed his tongue.

A new man—dashing and wearing much nicer leather boots—burst through the door in typical theatrics. He recognized his old lawyer and companion, Geoffrey Fieger, who had come after he’d heard of the doc’s death. He held his abdomen in obvious discomfort and popped an antacid in his mouth off a roll.

“Stop what you’re doing this instant!” Geoff demanded. His voice remained true to form, and its timbre even reverberated through the heavens. He grabbed the crumpled music and folded it out. “All of these things belonged to a great man, a visionary, and as his previous attorney and constant friend, I demand that his possessions be returned for proper storage and display. This was a great man.” The timid lawyer quickly bowed to him. Geoff brushed his fingers through his light hair and studied the music on the doc’s desk. At first, his face twisted from the perplexity. Doctor Kevorkian turned up the volume on the telescope so he could hear Geoff’s thoughts:

Jack. Jack. Jack. What were you doing here? Another vehicle of your madness? The music is interesting though. Elements of many classical composers. It’s oddly soothing. (Music begins to play in his mind and heart as he reads it.) This is . . . beautiful. I feel younger. My ulcer feels better. It really feels better. Jack, what were you doing? What is this?

Geoff dug through the notebooks on his desk, those not pilfered and destroyed, and he found the journal the doc had kept on his progress with the immortality invention. “Get out you idiots,” he yelled at the little lawyers and his cronies, and they obeyed, such was Geoff’s command in presence. Doctor Kevorkian listened as he recited all his notes in his head, listening to Geoff narrate the last great project of his life. He scanned it fast then reviewed again the music.

Jack went mad. God complex. But then, it feels better. He was a genius. He saw things in the ether. He saw things in human nature. It could be true. Had he really found something in the music? It’s possible. Nothing could cure that ulcer. It’s been burning for months with no relief, even bleeding. And the burn is gone. The music calmed him. It had to be tested. If it really works, though that’s insane, it could cure the world of death and suffering. Humans would become Gods, and God, obsolete. Imagine a world without religion. There’d be peace, real peace.

* * *

“You’re not just doing this for us are you, honey?” My mother asked.

“No. Of course not.” I lied. Of course I was. I never had time to cogitate whether I wanted to live, not like that, and I didn’t understand the Pyrrhic consequences for the rest of my life.

The cancer multiplied as good cells are supposed to do, this time going crazy, without parental supervision. I completed my chemo treatment, and it nearly completed me. I thought that had to be the worst of it—a few extreme treatments. I didn’t know the battle that would be coming. I didn’t perceive the charred demon faces that watched me in the autumn.

I have written about the Autumn People, though this is first time I name them in a published work. They dwell in the in-between places, between worlds, in the closets, in the shadows between doors and walls. You see them from the corner of your eye, always at the edge of the mirror, but they never come out entire. I see them now, always waiting, dwelling at the roots of oak and birch that sloughed their leaves and sleep silent for the winter.

The radiation gradually burned me—my head, neck and chest. They burned me in four mantles. Chemo just washed away new cancer. My doctors meant to kill the cancer already infecting me, up and down my neck and chest. I wouldn’t feel it, not at first. The burn would gather over time, through the next five months of daily treatment. They put me under that linear accelerator Monday through Friday. The technicians striped me naked, laid me down on the icy and sterile steel table like a specimen to be dissected. They taped my head down and shoved a wax bite into my mouth, which I had to hold and gag on for the next twenty minutes. I couldn’t move. The radiation passed through a specific lead pattern, each one designed for a different mantle of my body.

It would kill me—the death rays. It would take me along with the cancer, but it was my only shot. I let them do it to me. I allowed them to burn me. Every day I came to Center City Philadelphia, to the University of the Hospital of Pennsylvania, and I let them burn me.

I should have said no. I didn’t understand the life I would have to lead, the pain—the Price. I can’t turn back now, and much of the time, I desire to stop. Someone told me last night that I’ve already surrendered to the mechanisms of death, and it terrified her.

My throat swelled—the cancer dying, the scar tissue aggregating. It closed my throat, hindering my swallowing and then breathing. I had to keep going, or I would not survive. I struggled to complete my treatment.

I didn’t do it for me. I fought for the people around me as I watched them leave one by one. I refused to let anyone down. I dreamed while I was awake of stars. Moribund stars. Cinnamon just told me no one writes about dead stars. Cinnamon is a prostitute in my book, The Street Martyr, based on a real person. Cinnamon dreams of stars—alive and dead. It is their quantum state. We exist as dead stars.

* * *

Doctor Kevorkian watched as time passed, not taking his eyes off the events on the world below. Sometimes, he rewound back to previous moment to watch it again and again. As an outsider now to the stream of human events, he found it fascinating and gave it a divorced and dispassionate point of view as evolution changed because of his final masterpiece.

Geoff worked with a doctor friend to test and quantify the results of exposure to the song. At first, simple lacerations healed when exposed to the song, beautifully played by an orchestra Geoff hired in secret to record. Blood counts improved. Hair grew back. Cholesterol levels dropped. And male sexual dysfunction dissolved. Peckers shot up again! Jack’s music promoted greater blood engorgement of the male penis and the female vagina than had been recorded. Over the long-term, the doctors recorded its salutary effect on disease and discovered that gradually, heart disease, cancer, MS, Parkinson’s and any other kind of disease was turned back. The music boosted the body’s immune system to fight infection. And even more surprising, as the test results continued, they witnessed bodies growing younger. The music restored cells and arrested the effects of aging. However, the effect would only work on a living human. Cells divided from the body would have no response at all. It had to be a living human. It didn’t matter if they were deaf. They only had to feel the song somehow, even through vibration, to enjoy the rejuvenating effects of the song. Even coma patients responded, and one coma patient, Ms. Janine Gosford, woke out of her coma and wept when she discovered that she’d been asleep for twenty years, that her husband had left her and that she had no more children.

Geoff considered that health and a long life did not necessarily preclude happiness.

The results of the tests of Kevorkian’s new musical elixir far exceeded any of his hopes. Its power remained, even after the music stopped, and it turned out that once exposed, the music would continue to resonate in the cells, thus only one dosage was needed for the body to continue to repair itself.

* * *

In the parking lot outside of Saint Mary’s Hospital where Geoff and his staff had secretly conducted the tests, Ms. Janine Gosford waited for the lawyer to cross the lane, then she floored the ambulance she’d stolen out of the ER and slammed it into Geoff, throwing him off his loafers and into the hospital wall. She then wept and claimed:

“He’s the devil, that one! Smart-talking devil in Italian loafers! I miss my children.”

Geoff was initially shocked, and the kinetic energy of the ambulance that had transferred through his body shattered several ribs, his hip and the upper part of his spinal column. His liver was punctured, and he was bleeding internally. Hearing the commotion, orderlies came out to check, and they quickly fetched a stretcher and took the near-to-death lawyer into the ER. Before their eyes, they watched via scans and x-rays as his broken body repaired itself. Bones mended. Organs repaired. And he got quite an erection that made the nurses blush.

After this event, the secret was out. Doctors demanded to know what had happened to him, and the hospital wasn’t sure how to bill for their medical services, if even they could bill since his body had done the repair work. Whatever unnatural process had been unleashed onto his natural processes, it could have caused a complete collapse of the medical industry, causing chaos in certain financial circles. Finally, Geoff was forced to announce the breakthrough made by his late friend and client, Doctor Jack Kevorkian. Jack’s symphony would cure the world of death and disease, and thus it would cure war, poverty, hunger and all other darkness that haunted the race as a result of those two elements.

Ms. Janine Gosford had her driver’s license returned after twenty years then revoked again. She got into trouble for stealing the ambulance but claimed a temporary state of insanity. The hospital sued her, but Geoff represented her in court and got her off. She tried to kill him three more times, ruining two of his suits with blood stains, but she finally gave up and accepted God’s will.

* * *

And it killed me. The cancer didn’t end my life. The treatment destroyed my body, as was promised. I faded. I slipped into the running water of a river, and particle by particle, I dissolved into the currents, caught and drawn into the next world. I weighed at fifty pounds. The radiation destroyed my spine and brain stem, so I couldn’t walk. Much of my body numbed, as it has still. This became my end—no grand songs or epilogues, no speeches.

Drifting.

Drifting away.

Your spirit evaporates. It leaves first. Your body lingers behind, doing what it does by perfunctory program, by rhythm and natural design. My heart kept beating not through will or dreaming. It beat because it was hooked up to a power source. Nature builds sturdy devices, machines and mechanisms to endure. And then, it could suffer no more.

“I’d like to put a tube down your throat,” my radiation oncologist, Doctor Knight said.

“No. Gods no.” He wanted to examine my throat, the invading scar tissue. It sealed my airways. I’d suffocate soon.

“You need to do this, or you won’t survive,” my radiation-oncologist warned me.

I waited. I looked into the air, and I saw nothing but a vacuum of atoms. The procedure meant agony to me. I’d had enough.

I’D HAD ENOUGH.

That is the moment, the threshold of death. I felt this in my late teens. I no longer cared. I was done. I’d had enough. I just refused.

You are not choosing to die. It doesn’t feel like that. No one chooses to die. It’s not in your head to make that choice. It’s always something else. For me, it was choosing to stop the constant agony. I felt so tired. I didn’t care to be laid in wormy earth. I longed to turn the page, to see what came next. Curiosity desired my stay in the world. Still, I couldn’t endure the pain any longer. I refused any more treatment. I refused respirators and feeding tubes. I was done. No one could stop me.

You don’t ask to die.

You need the pain to stop.

* * *

Geoff delivered the Immortality Symphony—trademarked—to the world during a live and primetime television show featuring pop stars such as Justin Bieber, Rhianna and Bruno Mars singing it, and so simple was it that even the clumsiest musician could play it on any instrument. Soon all people, either through direct or accidental exposure, as the song became the number one hit in the world, played on radio, television and every New Orleans street corner, became immunized against death and all devices that could lead to expiration. Organs stayed open 24 hours and never closed. The heart beat steady. The lungs pulsed in rhythm. Cancer patients resigned their radiation, and crippled children danced in the streets.

Geoff, on his messiah popularity, naming himself the first prophet of Kevorkian, was named by popular election as governor then eventually president—but he had little to do besides organize parties, as without death and the need for food and shelter, war became extinct as a popular hobby. Geoff was named president for life, and he threw the best parties with all the current popular pop stars attending.

Life on the Earth changed. The old drive died. Folk stopped attending church and no longer followed any mainstream faiths. All the questions of life beyond death and cosmic meaning had been made obsolete. People didn’t have time to question divinity and the nature of the soul, not when better parties had to be planned, parties that no one on the block would forget. Pretty soon, the word soul was expunged from the MS Webster’s dictionary.

People, once good Christians, Muslims and Jews, danced naked in the streets of Baghdad, Paris, London, Bombay, New York, and even Levittown Pennsylvania where the author T. Fox Dunham had lived before moving closer to Philly then getting clobbered with an asteroid third. No one hated anymore. All loved. And no one was afraid.

They kept their collective peckers up.

* * *

Finally God had to enlist some of the angels, grabbing them from a poker game on one of the clouds, to drag Doctor Kevorkian from the telescope. He moaned all the way.

“It’s just not good for your adjustment. You have to let the Earth be.”

He never lost his dignity.

“There are other pleasures to partake of,” God said. He’d lost his left sandal somewhere and walked with one foot bare.

“I never cared for it. Gets in the way of the work.”

God sighed. And Doctor Kevorkian considered his future here in Heaven. “Though there are a few people I would like to meet.”

“Oh yes. Of course. We have many souls with plenty of time to chin-wag,” God said. “Anyone in particular?”

Doctor Kevorkian required no time to consider. The name shot into his head like a bullet. “Bach.”

“Johann Sebastian Bach, right? Didn’t he write some nice music?”

The Doctor stepped back, nearly tripping over his knobby feet. He covered his wide mouth with his palm. “Yes. He was the finest composer ever to live. He wrote to Your glory.”

“That’s nice,” God said. “I like nice music.”

“I have to . . . get away from you . . . now.” Jack elongated his words to express his frustration. He pushed off from God and climbed the clouds, searching for his hero, the composer Bach—the man who gave him order and logic. He searched the sky, losing track of time. Time felt differently in Heaven, when you no longer suffered or grew fatigued. The sun didn’t rise or set, and the air always cooled at a lovely seventy degrees—just right. God controlled the climate system and threw a few stars in the boiler to keep the place comfortable.

Finally, after searching endless cloudscape, Doctor Kevorkian found a length of pipe. It didn’t look like pumping infrastructure, and he noticed a lot of souls lingering from Bach’s time, speaking German. They swayed listlessly like zombies, not speaking or focusing their attention. He passed them by and strolled up to a great cathedral, when humans felt that stone structures mighty and fierce would earn the favor of their deity. Outside stood a bronze statue of his hero with rolling belly and white curly beard. Doctor Kevorkian heard no music, and he stepped inside the church and climbed to the stoop with a grand church organ. Pipes fanned out like spider webs from the engine. A tubby Bach sat in early period dress, waistcoat and coat, lace ruffles under his chin, and a curly wig dangling from his bulbous head. A single chord hummed from the lower pipes, and Doctor Kevorkian found Bach pushing down a few keys between his fingers, lost in mid-song. His eyes hung open, and he didn’t blink. He just stared ahead at a patch of stone in the Cathedral wall that held no particular property of interest or nuance. It wasn’t ugly stone, just unremarkable.

“Herr Bach?”

Bach declined to move, just gazed forward, searching the stone wall. Doctor Kevorkian kept back in reverence, afraid of displeasing this immense being in some way. He was awestruck at first then waited for Bach to make some sort of acceptance of his presence. At first, he wondered if the composer felt him worth to be in his company, but when drool fell from his fat mouth, the Doctor diagnosed him as comatose and began to check his vitals. He felt for a heartbeat and found no rhythm. He couldn’t check his breathing. Lungs were an illusion. Finally, he clicked his fingers around Bach’s ears, accidently hitting his noggin and knocking off his wig to reveal a large bald head covered in pimples.

“I’m terribly sorry,” Doctor Kevorkian said—all shy and concerned. He grabbed the wig off the floor and tried sealing it back on Bach’s head, but he couldn’t get it just right. He wiggled it about the ears, but he could never get the same style as shown in many of the old paintings of the era. Finally, he gave up. Bach just sat there like a fat Buddha sleeping. “I don’t mean to disturb you. I just have a few questions.” He nearly poked Bach in the gut then pulled back. Then the composer moved. He moved his head, opened his mouth and belched. Doctor Kevorkian smelled sausage in the air. Bach returned to his previous pose, leaving his fingers hanging off the organ keys.

“I’ll come back later, perhaps when you are less tired.” He leaned in and whispered, “I’m a great fan of your work.” Then he left and flew over the cloudbanks, looking down upon the old souls who waited in stasis like old statues. Some, he noticed, had even begun to erode away.

* * *

I lingered that October in hospital. They cut the radiation. My body could endure no more invisible rays. My throat nearly shut. Razors cut my neck and chest through every labored breath. I waited. I slipped away.

I don’t remember much. They brought me back. Two weeks of my life blacked out with God’s paint brush. I recall darkness. I’d like to lie to people when they ask me what I felt in my death, but all I only recall a vacuum. I demanded no respirators, but I still had some heroic measures in place—if there was a chance.

That’s all I can write about this, except it was Samhain—the pagan time of death and renewal, my new year. I had a tremendous sense of timing. I left the hospital after a month, finished my radiation.

They threw no party, no grand celebration for my remission. I felt like I deserved none. I lived. No one celebrates when you live. They just throw parties when you die. The machinery of Penn would grind on. New patients arrived, all clinging to the world.

It snowed that day I left. A little girl lay on a stretcher. I whistled as I strolled out of the ward, under my own power, some of my locomotion restored. The nurses hushed me as I walked out, and I realized this play would never end. The child ended. She finally slept.

They put me on notice. I had been spared. I never quite understood why I deserved it.

There are some places you never leave. I still worry that I’m dreaming, that I’m still sitting in that radiation oncology ward at Penn and in merciful, nepenthe slumber. Is this the dream?

I will go back one day. It waits for me. This is a temporary reprieve, and I am well past my deadline.

I owe fate a death. I intend for it to be a quiet one.

* * *

By the time Doctor Kevorkian had made it back to familiar clouds, to his point of entry, at least fifty years had passed by on Earth. To the doctor, it had only been an afternoon, a walk in the country. He called down to God, who stepped out of his solar nova throne, and the old hippie sat next down to Jack; and they both hung their feet over the edge of Heaven and let their toes wiggle in space.

“That was a disappointment,” Doctor Kevorkian said.

God sighed. “They get . . . bored.”

“Can’t you do anything about that?”

“I was considering putting in a swimming pool,” God said.

“Oh. That would be nice.”

“Still don’t know.”

“Oh.”

“It’s time. I shouldn’t have made time,” God said.

“You invented time?”

God hesitated and picked at a mole on his neck. He plucked hairs from the brown mass and tossed them into space below. “Well. To be honest, I took credit for time. I found it lying around the place when I took up office. Not a bad thing really. Without time, there couldn’t be changes.”

“But what if things stopped changing? Stasis? Static life? There’s nothing to look forward to here. Just oblivion.”

“I’ll install that pool, then,” God said. Doctor Kevorkian sighed. “You’re . . . just . . . not seeing it.”

“I’ve got other problems on my mind,” God said.

“I’m sure you have the whole universe on your mind.”

God folded his legs and sagged low, exposing his rolling belly. He plucked on his long silver beard. “We’ve stopped getting new souls in Heaven, and the old guard is getting bored. If this keeps up, everyone will be like Bach. And their energized particles will lose cohesion. Pattern will degrade. Entropy sneaks in. I found that one too. It came with time, so don’t blame me! Everyone blames me for too much. I’m not even there half the time.”

“No one is dying?”

“And it’s your fault. You found the infinity song.”

“But that was yesterday!”

“Fifty years. Your trip took some time.”

Doctor Kevorkian nodded. “My song cured death?”

“Doctors are obsolete. Priests are finding new jobs. Heaven will close without new souls. The last three we got in were writers, but they can only tell stories for so long until they start repeating themselves. Mandy DeGeit keeps ruining the few bars I installed, even though the liquor is all in her head. Max is moody ‘cause he misses his girlfriend, Lori, so he’s no fun. And that Fox guy? What a Me-damn maniac! He won’t stop. He’s upsetting the natural order of the place and keeps hitting on the nuns. The guy has to be stopped. We need new souls.”

God threw down a handful of birdseed into the clouds, and angels swooped down and scooped up the seed with their lips. They skulked about like pigeons, cooing and singing. God didn’t seem to notice.

“What can you do about it?”

God shrugged, and Doctor Kevorkian felt an ancient and soul-crushing despair. His skin faded gray, and he hung his head over, ready to fall. Then he considered, going back to his old ways and means. “Well if it’s coming, we should offer it to some of them faster. End their existences. It would be kind.”

“That was your shtick on Earth, wasn’t it? Something about euthanasia and all that hubbub?”

“That was my cause. And it failed.”

God reached to touch him, to reassure the soul he had woven and created, sown life, love and agony into his heart. But, he held his hand back and withdrew it onto his lap.

“I could just put in a pool.”

Doctor Kevorkian sighed.

* * *

Janine Gosford’s life ripped wide like a great red canyon on Mars. Her doctors put her on all sort of pills and antidepressants, which she swallowed down with great bowls of ice cream melting in pools of lager. She worked every day as a typist at Geoff’s at the White House for President Geoff, and she found companionship when she needed it, often in the form of interns looking to get ahead or a male escort service that serviced exclusively to women of size or those who were born without the notable features displayed in many pop magazines and movies.

And she sighed the days away, returning home to an empty apartment, feeding her seven cats—and she decided it was time to build a nursery in the guest bedroom and add to the population of the planet. This act had become less of a hobby when the current species was granted immortality, and already space issues consumed the few remaining governmental bodies, such that since people could no longer die, they considered launching them into other worlds such as Mars. The quality of life would fall, but eventually with enough people using their noggins and the industry that made the United States so great—beating the Nazis and stuff—they’d soon have the gross national products of Jupiter and Mars up to standard and would improve the quality of life. Rockets would only be needed to jettison people out of Earth’s orbit, where they would drift in space, quite comfortable—much like sleeping in a womb—until their predetermined trajectory would land them on one of the outer planets of the solar system.

The people supported this plan, and the parties were never so crowded and swinging in the District of Columbia. They praised President Geoff and forgot all about Doctor Kevorkian—the man who had changed what it was to be human. Sans death, they required no faith. Religion, atheism and many of the major philosophies died like so many raccoons under car tires. The cosmic questions still existed, but they no longer had relevance over humanity; and more so, immortality obviated the fear of death; thus, sans such fear and insecurity, no more did preachers and reachers require conversion to their dogmas. Before the rampant immortality, even the most obsessed zealot buried a clandestine doubt and needed to convert others to be reassured by majority opinion. The old antagonisms of faith fell away. No more did extreme members of Islam go a-merry jihading. White supremacists kissed yarmulke, and Christian extremists no longer bombed abortion clinics—killing doctors, staff and mothers in the name of the preservation of life. Not only peace between nations but also accord between people was reached. As civilization stopped progressing, so did war, and most considered the transaction acceptable.

So Janine Gosford drove her scooter to The Nicholas Cage sperm bank in Richmond Virginia, where you were guaranteed to be impregnated with a child that looked just like Nicholas Cage. She went in and ordered one specialty-Nicholas-popsicle, which she took home and thawed in the sink like she used to with hot dogs, before the song had cured her of hunger. She let it melt then sucked up the goo with a turkey baster. She put on her favorite Nicholas Cage movie, City of Angels, closed her eyes and felt his hands feeling down her fat neck and tits, moving lower into her cunt where his fingers tickled and knew just where to play. Then she injected the syringe and pumped Nicholas deep into her womb. Then Janine sat on the couch, stuck her hips around her neck so gravity could soak the sperm into her egg. Now she waited to be a mother. She waited to be fulfilled.

She kept Nicholas’s pecker up for him. In this case, she employed a turkey baster.

She waited, and every night she tested herself with a urine wand to find out if she was indeed carrying a new life. The wand continued to show negative results, and she sucked back a cup of Jack and slept through the evening. Finally, she went back to the clinic and protested their defective product. She complained and screeched, and they gave her another vial of Nicholas, which she promptly went home and stuck up her vagina and squirted.

This problem was occurring across the United States. The world existed in peace and physical needs had been removed. What a perfect time to start a family. Surplus population could be shot into space to pursue their destinies there or live in the harsher climates of Antarctica and desert regions. However, potential parents discovered their efforts were consistently failing. Finally, doctors were called back from their retirement. They did their tests, scanned with their scanners and pendulums, and they determined that healthy wombs had shriveled up to the size of a grape. They could no longer harbor ovum, probably because humans no longer needed to continue the species through physical reproduction. Evolution had countered, and wombs had gone obsolete.

Janine Gosford was the first to sign a class-action suit against President-for-life Geoff and the estate of the late Doctor Kevorkian. Soon thousands of people across the planet signed on, and President Geoff found himself facing impeachment. He had none of the other customary devices which presidents resorted to when facing political disaster—no scandals to blame or scapegoats or wars to start. He couldn’t attack another nation. There were no standing armies. The old systems had fallen away.

When humans learned that they wouldn’t be able to have children, the parties stopped. All the bars closed. The churches opened again, and medical research began. President Geoff promised a cure song would be found, one that would undo the damage brought by the Kevorkian Infinity song. It held the bloodthirsty people at bay, but soon the mass suffering overwhelmed the masses. Courts convened, and since money had been done away with, the lawsuit declared President Geoff’s life as payment. It would help little to absolve the suffering of the couples and singles denied offspring, but at least they could watch him suffer. This provided some incentive, motivating scientists to discover a new way of ending an immortal life. The intellectual community researched and experimented, but most options such as fire, poison and ice had no long-term effect. There were many test subjects who volunteered, longing to end their suffering. If the lost ones could not satiate the void inside their souls, they’d join it in oblivion.

Finally, looking back to the Cold War, it was determined that if President Geoff were strapped to an atomic bomb, it should vaporize every cell of the human body simultaneously before the body could regenerate. If this test was successful, there were signup sheets printed for those who wanted to end their lives.

A use had been found for all the atomic weapons left to rust in warehouses, and bomb- making plants would once again have function. The people rejoiced. The atomic bomb business flourished, offering the only remedy to common immortality, and it soon dominated all other industry, become the main export of the United States and The Russian Federation. Personal atomic devices, once miniaturized as suitcase bombs, became available for home use. Normally measured in kilotons, scientists refined the chain reaction down to merely tons, thus making home use practical. Companies like the Lansdale Atomic Bomb Company of Lansdale PA manufactured this new remedy and hired the marketing firm of Deal, Drake and Gill—a firm set up specifically to put a friendly face on the stigma of atomic weapons—to market it. The firm came up with a marketing plan that painted friendly feline faces on the plutonium cores at the center of the home devices. They advertised the bombs as medicine, remedies and ran commercials on the internet:

The world has changed. People no longer get sick. They no longer die. It is a time of miracles. And now studies show that at least thirty percent of Americans suffer a new form of depression, which doctors are calling Post-Immortality Syndrome or P.I.S.

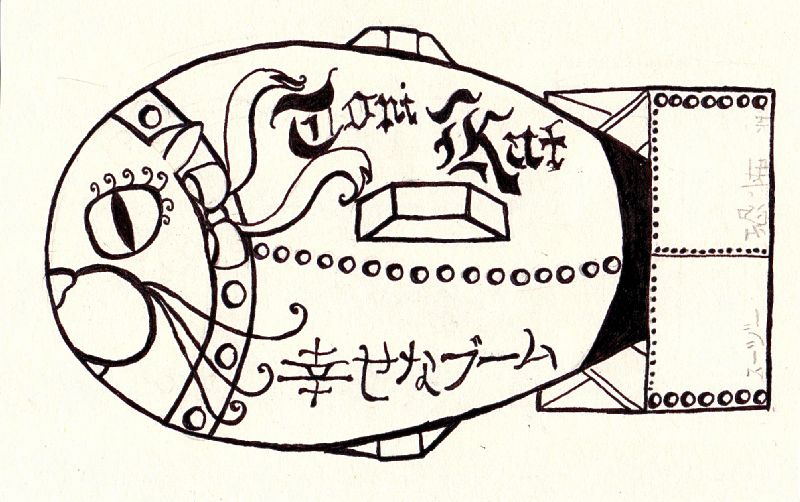

Scientists and medical professionals at the Lansdale Atomic Bomb Company of Lansdale PA have worked hard to create a new treatment so Americans no longer have to suffer. Introducing The Toni Cat Nuclear Home Kit. Just one application of the Toni Cat, and it will cure your depression and prevent any relapse. Just take one dose of Toni Cat to any clearing of at least two miles and apply. Comes in twenty, ten and five tons.

Guaranteed to cure those cloudy-day blues.

Here is a rough drawing of the kitty face painted onto a plutonium core.

This cure brought remedy to the lost, ending their pain. They’d kept their peckers up, and their faith was rewarded.

* * *

Doctor Kevorkian worked through the days, careful to watch the sun so he could track time. He wandered about the clouds, always keeping to himself, always busy working on some wild project and never relaxing. He kept constant observation on his phantom flesh to make sure he hadn’t begun to fade. He kept envisioning those folk from the clouds around Bach’s Cathedral—slowing turning into statues then fading into the ether, into nothingness. He shook thinking about it, and he set to work, keeping his mind busy, his soul at motion, so his energy wouldn’t phase out.

Eventually, his spirits fell, having nothing useful to contribute to his existence or the universe. His efforts in compassionate euthanasia had gone down a cultural cul-de-sac. He’d made no great change politically in human affairs, and it looked as if his final invention, the Kevorkian Ninth Symphony, had ended all human endeavors along with its ability to procreate. The human race just stopped, falling into prolonged stasis.

Finally, one day, Doctor Kevorkian sat down on a cloud bank and just stopped. He was almost ‘done.’ His ethereal body started losing cohesion as his will dwindled, and he faded. God saw this and worried for his new friend, so he arrived to try to cheer up the old doctor.

“Doctor?” God said.

“Yes God? What . . . is . . . it? I’m very busy, you know. A man has got to have some privacy once in awhile.”

“I just thought you might like to meet some folk. The ones you helped. They wanted to say hello when they heard you were here.”

One-hundred and twenty souls lined up. Doctor Kevorkian had ended the pain of their mortal lives, emancipating them. They queued up in the order of their deaths, and each wore that number on his or her hand.

“Oh. That’s not necessary.”

“They just wanted to say hello,” God said. “I shall let them through.”

Doctor Kevorkian humbled and hunched his shoulders over. He smiled and wore his kind eyes as the people came through.

Number one stepped up. Janet A. hugged him, squeezing his thin frame. Her mind was clear.

Number two followed her. Sherry M. danced to him and kissed his cheek.

Marjorie W. smiled and waved.

And so this went on—all the love they shared and gave him, all the sick and suffering he’d cured, emancipated from the imprisonment of their own bodies and sentences imposed upon them by an iron-morale society. One-hundred and twenty souls gave the kind little rebel their eternal love and gratitude. His soul renewed.

* * *

On Earth, the trial convened, and the jury of one-hundred and twenty peers found President Geoff guilty. They didn’t have a law to try him by, so they just declared him guilty as sin. He suffered the verdict with dignity. He’d had a good run, tried good law, helped friends and fought causes. Now, he could lay down his head with some dignity and not worry anymore about the stagnation of the human race.

Retired US Marshalls drove President Geoff out to the Nevada proving ground, where the Atomic Energy Commission had placed a single two megaton Super Toni Kitty thermonuclear bomb in the back of a truck. One single human was allowed to act as the trigger man, and a lottery was held for all those who wanted to die. That lottery was won by none other than Janine Gosford, who felt it an act of God—even though God wasn’t really paying attention, too busy trying to cheer up Doctor Kevorkian.

They tied President Geoff to the warhead with sensual Japanese ropes. He wore his best suit and had his hair done for the execution. He had to keep up appearances for posterity in case time ever began again.

Janine Gosford wore her best dress and pumps. She’d done her face up with makeup and looked pretty to President Geoff. “Mr. President,” she said and curtsied.

“I never meant for any of this to happen,” he said. “I was just trying to help.”

She grinned. “I know, Mister President. I know. That’s why I’m glad there will be no pain.”

She primed the trigger, a small button on a pad in her hand. They made it simple—a single button would detonate. She gave the army time to clear, and they waited in silence. The sun began to set. Finally, she held the button, kissed Geoff on the lips and pressed it. The last sight he saw in the mortal world was a smiling kitty face.

He died with his pecker up.

* * *

Doctor Kevorkian painted during the days, trying to concentrate. He considered the problem of atomic bonds and energy frequencies that formed souls. He painted on the backs of fugue souls, just standing there in the clouds and swaying in the light wind. He painted portraits of angels bound to crosses with piano wire cutting into their wrists and ankles, slicing into their flesh as they looked low to the world and wept. He also painted a dog skeleton running home to his master. He called the dog Neal.

God lumbered over and opened a beer. The suds foamed up and ran down his stubby fingers. He sighed. Heaven had gone quiet. No action. The choir had stopped singing. The shops had closed. The souls hung about with their mouths hanging up with drool draining down their chests.

“This place is deadsville” God said. “I looked into putting in a swimming pool. No one seems interested.”

“That’s because they’re zombies,” Doctor Kevorkian said, gritting his teeth at being interrupted. God kept hanging out on his cloud, commenting on his painting, eating his munchies.

“Earth’s not much better,” God said. “They blew up that lawyer of yours. Atomic explosion.”

“Good for him,” Doctor Kevorkian said. “He always knew how to make an exit.”

“They’ve started blowing people up on Earth, but the energy messes with their atomic bonds. It changes the way their strings vibrate. M-theory. Turns the harp into a cello. Off they go. They’re not coming here. I’m not sure where they’re going.”

“Earth’s really going to hell,” Doctor Kevorkian said. “Don’t know if anything can be done about it. Heaven with it.”

“If only we could talk to them.”

“Why don’t you give them a call?”

“I can’t,” God said. “Each time I try, it causes earthquakes or plagues. I burn with the raw stuff of creation, and I change and disturb anything I interact with. So no go. Last time I tried, the Dark Ages happened.”

Doctor Kevorkian returned to his art, letting his mind wonder. Paint covered his hands. He smeared them down the nebulous fabric of the cloud, decorating the fluff in gray and browns and red smears. Some of it leaked on God’s toes, but he didn’t seem to mind. Doctor Kevorkian started a new canvas and painted a crucifix. He stopped in mid-brush stroke and looked at God.

“Was he really your son?”

“You are all my children,” God said. “From Buddha to Jesus to Pontius Pilate . I gave you all a mote of my heart. But it’s a great heart. I just don’t notice things most of the time. I’m a big picture sort of God.”

“Yes. I can see that, but my point is, you don’t have to go. You could send someone else to Earth. I mean, you did it before?”

God’s eyes lit up with lightning strikes behind his irises. Doctor Kevorkian felt the thunder rumble through the clouds. “It didn’t work so well the first time, but we could try it again. It’s got recognition, power now as a symbol. If someone could just tell them to have faith, that I do exist and love them. That they can solve any problem if they don’t lose hope.”

“Is Jesus available?”

“Not that one,” God said. “He faded centuries ago. He got so bored. And I think . . . he was heartbroken.”

“Whom did you have in mind?”

* * *

The Atomic Kitty Party kit. Comes complete with snacks, booze, jukebox and a heavy Toni Kitty Nuclear Remedy device. Dosage strength: one kiloton. Guaranteed to provide the best mass vaporization party on your block.

* * *

For centuries, scientists still tried to remedy the problem of reproduction. One company even developed a plan to cook a baby in a microwave. You just put an ovum and some sperm into the bag, added water and certain spices, and popped it into the microwave. And bam. Baby. Of course, you could burn it if you put it in too long, and they had problems because when the children were born, they smelled of butter and popcorn, so it didn’t work out well—and of course, none of the grown fetuses functioned.

Since humans could not give birth, Doctor Kevorkian could not return to earth the conventional way; so God stuck reborn-Kevorkian into the womb of a walrus, and he was born on the coast of Scotland three hundred years after his death. The world had changed little. All progressed ceased. And millions of humans, who had been shot into space, filled the void between earth and Mars, slowly floating there to make a new life.